In Dickens' famous portrayal of life in the workhouse, Oliver Twist and the other children in the workhouse live a life of cruelty and neglect. In a now iconic moment, after drawing lots, Oliver bravely asks for more food (even though this food is a rather revolting sounding gruel - a food that has come to be synonymous with the idea of the deprivations of living in the workhouse). Dickens describes Oliver's diet as consisting of 'three meals of thin gruel a day, with an onion twice a week and half a roll on Sunday'. On feast days, however, the inmates were served an extra two ounces or 60 grams of bread he tells us. But what do we actually know about the workhouse diet for children and was it so awful?

The menu here for children aged two to three years comes from the workhouse in the Rhayader Workhouse in Wales. We can see a rather repetitive menu on offer, which is carefully measured in terms of quantities. Keeping an eye on costs would have been as important then as it is now in institutions. Unlike the menu on offer in Oliver Twist, the diet is not one of gruel, gruel and more gruel (with occasional bread and onion), we can see milk, different meats (mutton and beef), vegetables, and bread and butter. A little soup and rice pudding also make an appearance.

The food on offer for children would have differed to that of adults, primarily in terms of quantity as you might expect. Jonathan Pereira's Treatise on Food and Diet with Observations on the Dietetical Regimen - was adopted throughout England in 1836. The book was expressly designed to address the diet that should be given to 'paupers, lunatics, criminals, children' and 'the sick' - those in institutions such as prisons or the workhouse. The table here shows his calculations of food for men, women, and children over the age of nine years. it is interesting that they are deemed to need the same amount of food as women. The diet might be stodgy and monotonous, but it was certainly more interesting than the diet of Oliver Twist!

When thinking about paupers (i.e. those who would have lived in the workhouse), Pereira argued: 'It has been very properly stated by the Poor Law Commissioners, that in the dieting of the inmates of workhouses, the object is to give them an adequate supply of wholesome food, not superior in quantity or quality to that which the laboring classes in the respective neighborhoods provide for themselves' (p. 236). The food was meant to be 'wholesome' but not better than working families could afford - it might, after all, serve as a disincentive to work - or so it was thought (Miller, 2013).

Smith et al (2008) conducted a dietary analysis of Oliver Twist's diet from the novel and in a headline grabbing article calculated that it would be insufficient in nutrients to maintain health and growth, and would have resulted in diseases linked to nutritional deficiencies such as beriberi, rickets and scurvy. However, the diet put forward by Pereira would have been sufficient, they suggest, to maintain a healthy child aged about nine years (unless exceptionally active). Of course, it is problematic to equate Oliver's potential health with that of children today as the researchers note. He would, after all, have been undernourished for his years and would have needed to catch up on growth - but then again, he would have been smaller most likely and so might have needed less food. It is hard to say, and of course and 'Oliver' is a fictional not real child.

Ian Miller (2013) notes that there were regional variations and in some workhouses the staff were overzealous in minimising the portions given. Thus, he argues it is very difficult to assess the workhouse diet across the country with any precision. Poor Law commissioners were tasked with ensuring paupers in the workhouse did not starve to death, rather than concerning themselves with the intricacies of nutritional requirements (such as were known at the time). And as there were no guidelines for feeding children under the age of nine in England, the diet of these children was at the whim of individual medical officers and workhouse masters. Once nine years of age - when regulation of their diet came into full force - their diet might even have been reduced if the workhouse master had been kindlier in his portion allocation for young children where no such regulation existed.

Where Dickens hits a chord is in turning our attention to the harshness of institutional life for children. Children would have been split from their families on entry to the workhouse (assuming they had older relatives), unless very young. Older girls would have been separated from older boys. Families may have been granted a daily 'interview' with their children, but the idea that they might eat a meal together was very far from their experience. Miller (2013) notes how meals were strictly timetabled, inmates had to queue for food (sometimes the food became cold), and then they had to eat in silence. Disciplining the bodies of those in the workhouse was clearly meant to instil a sense of self restraint it seems. Food was even withdrawn from children (in particular) as a punishment to keep them in line.

But we need to remember that things did change over time. As greater medical knowledge was bought to bear on the workhouse diet, coupled with shifting ideas towards poverty that saw it less as related to idleness amongst the poor, the idea of the workhouse transforming the health of citizens became more important. The Poor Law Board appointed Edward Smith to compile a report on workhouse dietaries (published in 1867) and he was especially keen to ensure children were well fed to enable them to grow up strong and healthy, able to earn a living in later life rather than being a recipient of welfare (Miller, 2013). It was still an environment, which families feared having to resort to, however.

In writing Oliver Twist, what Dickens did do is encourage his readers to think about the lived lives of impoverished children - their diet being one aspect of this. It is Oliver's harsh mealtime experience as much as the diet on offer that leaves a lasting impression as it so very far removed from meal experiences in a nurturing environment that we would hope for all children. It is hard to assess whether workhouse children under nine in England received an adequate diet is hard to assess as they did not come under any guidelines. Thankfully, the workhouse is consigned to the past, but there are still many children whose families cannot afford an nutritious diet. It is an issue of social (in)justice that clearly needs addressing even in the 21st century.

References

Dickens, Charles, Oliver Twist, (London: Penguin - first published 1837-9).

Miller, Ian, 'Feeding in the Workhouse: The Institutional and Ideological Functions of Food in Britain, ca. 1834–70', Journal of British Studies , 52 (4) (2013): 940-962.

Pereira, Jonathan, and edited by Charles A. Lee, Treatise on Food and Diet with Observations on the Dietetical Regimen, (New York: Fowlers and Wells, 1843).

Smith, L., S. J. Thornton, J. Reinarz and A. N. Williams, 'Please, Sir, I Want Some More', BMJ: British Medical Journal , 337 (7684) (2008):1450-1451.

Image credits (in order as they appear)

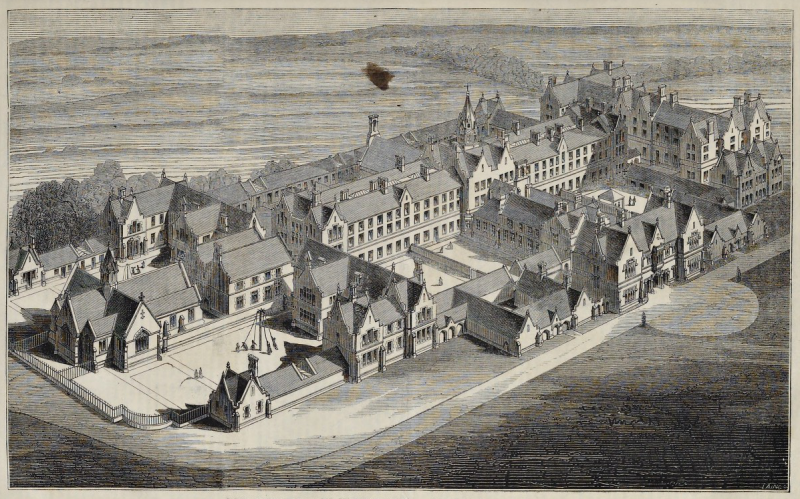

Birmingham New Workhouse, 1852 uploaded from Wikimedia Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Birmingham_New_Workhouse,_England,_c.1852.png

Rhayader workhouse diet for very young children, https://www.history.powys.org.uk/school1/poor/poordiet.shtml

Dietary (Deb Albon photograph) of Jonathan Pereira's Treatise on Food and Diet with Observations on the Dietetical Regimen (p. 240).

Charles Dickens from Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dickens_Gurney_head.jpg

Add comment

Comments